Gnosis and the Noosphere

Spirit versus Matter: The Great Debate

It’s possible to spend so much time in your head, you lose touch completely. After a long enough spell of inner darkness, the line between delusion and ultimate reality will dissolve. Some call it insanity. I call it human—forgivable, but all too human.

My book is entitled Dark Aeon as an homage to big “G” Gnosticism, as well as its vapid little “g” imitators. The ancient Gnostic tradition gets its name from the Greek term gnosis, or “spiritual knowledge.” Gnostics then and now describe gnosis as a direct experience of the divine—as opposed to mundane or scientific knowledge. In its Christian forms, Gnosticism was declared a heresy and stamped out by the early orthodox Church, which insisted upon pistis, or “faith.”

On a superficial level, Gnosticism is a freethinker’s rebellion against worldly authorities, from ancient Rome to today’s scientific materialism. It’s a quest for absolute liberty, embracing forbidden possibilities, even at the risk of moral pitfalls.

As I explain in my chapter “Virtual Gnosis,” there are strains of transhumanism that resemble Gnosticism. A few are directly inspired by it. In terms of philosophy, however, transhumanism is diametrically opposed to Gnosticism. The former seeks to transcend the material body using science and technology, allowing humans to transition into some higher physical form. The latter seeks to escape the material world entirely, using ritual and meditative discipline to return to the pure spiritual hierarchies, called Aeons.

Setting dogma aside, one can imagine religious orientation on a spectrum. On one side is dynamic matter; on the other, pure spirit. There are countless degrees in between. On the material side are hedonists and oppressors who live for today, absorbed in things of this world. On the spiritual side are ascetics who suppress their sexual urges and violent passions, retreating to a monastic life with an eye toward eternity.

The early Gnostic texts were aimed toward the spirit. In many instances, Jesus is portrayed as a purely non-physical being coming to liberate “cold wayfaring strangers” from this material world of woe. Practitioners seem to have exhibited various degrees of self-denial—even if some groups indulged a tantric path—seeking a higher Being beyond outward forms. They took the Christian suspicion of cosmic “powers and principalities” to the extreme.

Transhumanism is not Gnosticism. To conflate the two would be as misleading as James Lindsay’s “Marxism is Gnosticism” formula. If the good doctor would like to debate this in public, I’m right down the road. Let’s see if his cheap, algo-boosted gimmick can withstand real scrutiny. But more on that in a moment.

Some forms of transhumanism do aim to escape the fragile body into a purely digital realm. This is a materialist distortion of Gnosticism—a reflected inversion. You don’t get more material than implanting chips in your brain, or building heaven (and hell) within data centers.

My writing on this, based on years of study and personal relationships with actual Gnostics, is an attempt to clarify the subject. In our trend-chasing online culture, “Gnosticism” is now code for “things I don’t like.” It’s a trigger-word for torch mobs. You might say “Gnosticism” is the new “racism.” Once you’re woke, you see it everywhere.

To be clear, I am not a catechized Gnostic. My own heterodox spiritual commitments are explained in my chapter “Images of Jesus: A Confession.” But I’m not a witch-burner, either. Purity spirals aren’t my style.

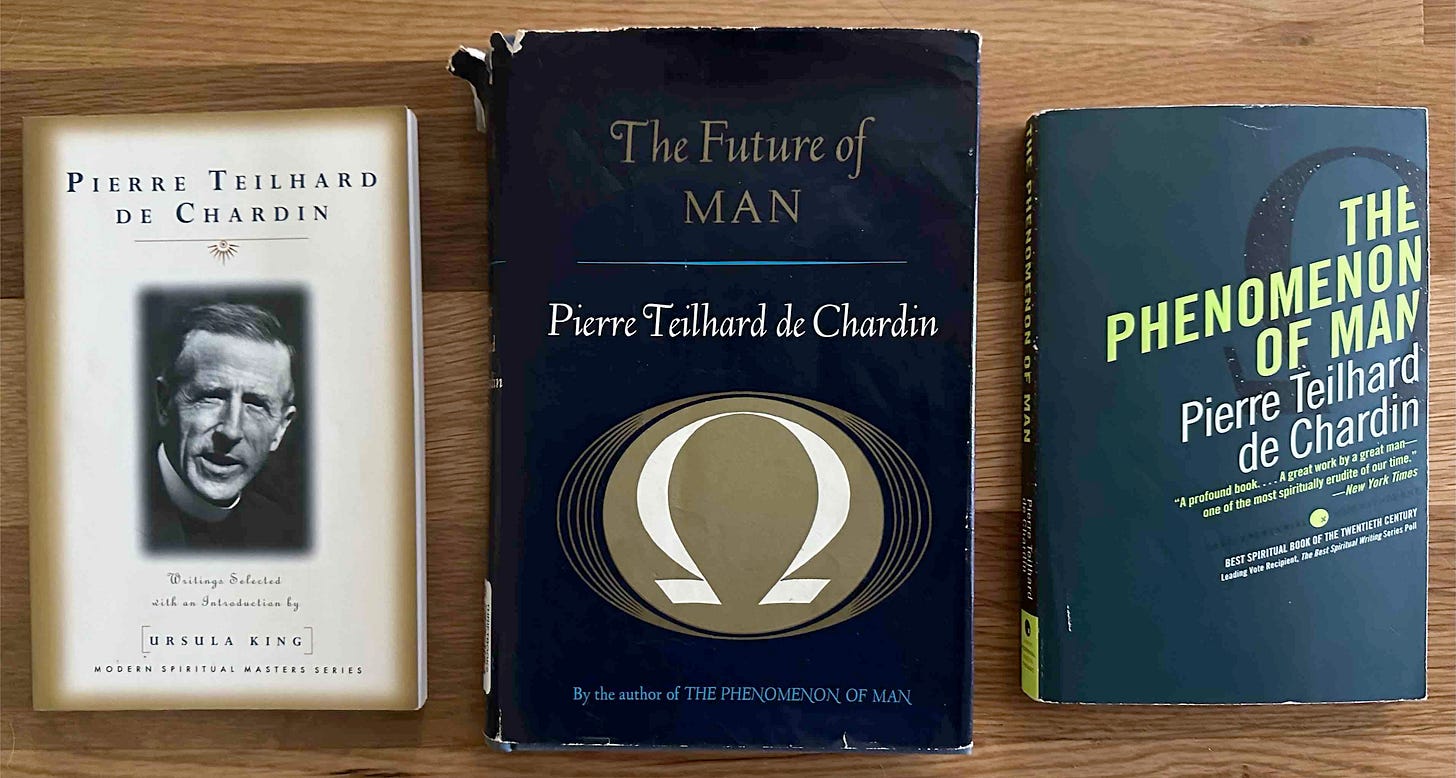

My new podcast is called Omega Point because that vision of the future—put forward by the Jesuit priest and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin—presaged the technological Singularity. Teilhard was an early adopter of the term “transhuman,” writing in 1949 about “Liberty: that is to say, the chance offered to every man (by removing obstacles and placing the appropriate means at his disposal) of ‘trans-humanizing’ himself.” Perhaps he was inspired by Dante’s use of trasumanar in his Paradiso.

Teilhard’s good friend Julian Huxley would make the term official in his famous “Transhumanism” lecture, first delivered in 1951. Four decades later, Max More would make it a household name.

Make no mistake, I’m as opposed to Teilhard’s techno-optimism as I am present-day transhumanism. But it’s foolish to dismiss these worldviews without thinking them through. If you prefer that convenience, go watch Fox News or MSNBC—or maybe listen to New Discourses.

The Omega Point was Teilhard’s attempt to reconcile his religious faith with the theory of evolution. It’s an apocalyptic vision in the original sense: the old world will pass away and the new will be revealed, even as new light sanctifies old forms. For Teilhard, “directed evolution” is being drawn forward by a unifying force, out in the future Omega, which he identified as the love of Christ.

For about a century, Teilhard drew the ire of Catholic authorities—which forbid him from publishing his visionary work—as well as the scorn of hardcore Darwinists. Similar to the Gnostics, Teilhard believed in radical human freedom, even if he believed such freedom would naturally lead to cosmic unity. Contrary to the Gnostics, and more in line with his orthodox Church, he had faith that the material world of rocks, cells, plants, animals, and human beings—including our technology—would all be sanctified by God.

The Omega Point is not Gnosticism. Certain early Gnostics viewed the material world as the flawed creation of a half-blind Demiurge—an ignorant deity convinced he is the highest power—and saw physical forms as inherently flawed. Teilhard viewed the material world as clay that God was gradually shaping into a cosmic image of Christ.

Teilhard’s magnum opus, The Human Phenomenon (often translated as The Phenomenon of Man), was based on the science of his day. But the real theme is his mystical vision. The book is an epic poem composed of tongue-twisting neologisms. Aside from the Omega Point, his most enduring jargon was the term “noosphere.”

As you’d expect of a paleontologist, Teilhard saw the earth in terms of layers: the rocks of the lithosphere are overlaid by the plants and animals of the biosphere. With the rise of humanity, he observed, we now see the emergence of a new layer: cities, written texts, artwork, statues, and currency—human ideas manifested in material form—along with the roads, sea lanes, radio waves, and telegraph cables that connect it all.

Teilhard called this cultural layer the noosphere, from the Greek term nous, or “mind.” This was the purely human thought layer, formed by a web of materialized information—a sort of nervous system developing around the planet. Fifty years later, early Web-enthusiasts would see Teilard’s vision as a prophecy of the internet. Our planet is a superorganism “clothing itself with a brain” as Wired writer Jennifer Cobb Kreisberg put it in 1995.

This vision of an interconnected noosphere drawn toward an Omega Point had deep impacts on later thinkers, ranging from rigorous theorists like Marshall McLuhan, Kevin Kelly, Robert Wright, and David Sloan Wilson to the loosey goosey world of New Age gurus seeking to add a spiritual dimension to mechanistic evolution. The latter includes a handful of Theosophists. But labeling Teilhard as such would be as misleading as saying Marx was a “Gnostic.”

Teilhard is often misunderstood as a totalitarian collectivist. That’s a lazy reading of his work. Being a stretcher-bearer in the first world war, he had direct experience of mass violence. As he wrote around the time of the second world war, the rise of communism, and the fascist response, were abhorrent to him. Such conformity was a “profound perversion of the rules of noogenesis.”

“We have ‘mass movements,’” he lamented in The Human Phenomenon, going on to describe them as “‘the Million’ scientifically assembled. The Million in rank and file on the parade ground; the Million standardized in the factory; the Million motorized—and all this only ending up with Communism and National-Socialism and the most ghastly fetters. So we get the crystal instead of the cell; the anthill instead of brotherhood. Instead of the upsurge of consciousness which we expected, it is mechanization that seems to emerge from totalization.”

Striking a techno-optimistic note, Teilhard’s suggested response was a mere “determination to re-examine ourselves.” That’s a noble sentiment, but I think it’s hopelessly naive. Despite his gentle disposition, the Jesuit scientist had a technocratic streak a mile wide, he was Eurocentric to a fault, and displayed a galling indifference to ecological devastation. He couldn’t see the Machine as being destructive by its very nature.

Teilhard was human-centered to his core. So I wonder what he’d think about humanoid robots, killer drone swarms, and artificial intelligence—or even couch potatoes drooling in front of their TVs.

Teilhard may be the forebear of transhumanists and Singularitarians, but most of them either discard or obscure the Christian trappings of the Omega Point. Some have rebranded the noosphere as the “global brain,” the “holosphere,” the “technosphere,” and so on. The most extreme are using the priest’s fire to forge a new race of robots.

The Greater Replacement really is a perversion of “noogenesis.”

In 2020, I had an intense encounter with the modern Gnostic revival. That summer, while the world descended into hivemind insanity, I attended my longtime friend’s ordination as a deacon in the Ecclesia Gnostica. He is now a priest. This renegade Gnostic church was founded by Bishop Stephan Hoeller. Being a Hungarian immigrant who’d experienced Nazism and Stalinism firsthand, Dr. Hoeller reveres American freedom. He’s a fierce opponent of communism, fascism, Scientism, or any groupthink “-ism” that might constrain free thought or a free conscience.

The following year, I had the pleasure of meeting Hoeller at a large Gnostic gathering, alongside many others in this subculture. If there’s one thing that defined the vibe, it’s a strange blend of refashioned Catholic liturgy and total mental freedom. There was no single shared dogma. In fact, no one seemed to agree on much of anything. Politically speaking, some were right-wing and some left-wing. Many were indifferent to politics. Some were morally conventional, others libertine. Most were good-natured. A few were rotten egomaniacs.

In short, these modern Gnostics were as diverse as they were thoroughly human. I never feel completely at home in any religious gathering—or anywhere else for that matter—but I always appreciate being received as a welcome visitor.

The year after that, at a 2022 American Freedom Alliance conference, I met James Lindsay—the New-Atheist-turned-Christian-Apologist(-but-still-atheist?) Twitter personality. He struck me as a well-spoken critic of the globalist system, albeit narrowly obsessed with the Marxist threads. I’d soon learn of his flimsy theory that these Marxists were actually “Gnostics.”

Lindsay is rehashing the “Gnostic accusation” leveled by the political philosopher Eric Voegelin over six decades ago. By the late 70s, though, Voegelin would have the self-possession to admit this was an imprecise comparison. So far, Lindsay seems hellbent on digging a hole so deep, he’s liable to fall out the bottom of our flat earth. Maybe he thinks there’s gold down there.

Throughout the AFA event, I’d see Lindsay huddled under the wing of his benefactor, Michael O’Fallon. The latter takes credit for awakening Lindsay to the true nature of the Ultimate Conspiracy.

According to this duo’s combined framework, the One World plot involves an unnamed cabal doing “psy ops” through a “Hegelian dialectic” that deploys “Marxist,” “Gnostic,” “Hermetic,” “Neo-Integralist,” “Communist,” “Fascist,” “Technocratic,” “Transhumanist,” “Transgender,” “Theosophist,” “Socialist,” “Globalist,” “Anti-Racist,” “Antisemitic,” “Nationalist,” “Racist,” “Foundationalist,” and “Luciferian” ideologies, utilizing an “Alchemical” process of “Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis”—otherwise known as an open-ended conversation—to control the masses through hubs like Harvard, the UN, and the World Economic Forum.

Something like that.

As far as I can tell, the only people not tainted by this sinister “Hegelian dialectic” are James Lindsay and Michael O’Fallon, plus a handful of high-profile podcasters and influencers, a few super-rich megachurches, Wal-Mart, Starbucks, gay marriage advocates, and some NPR show called “Classical Liberalism.” Maybe I’m forgetting somebody.

For all their bluster about the “woke” smearing anyone they don’t like as “racist,” “sexist,” and “homophobic,” it would appear O’Fallon and Lindsay have co-opted their method—using trigger-words to flatten complex people into one-dimensional boogeymen. The charitable interpretation is these two are so egotistical, they simply can’t see what they’re doing.

A conspiracy theorist might suspect they’re paid gatekeepers, tasked with policing the boundaries of acceptable discourse. Any time someone expresses an interesting idea in public, Lindsay’s algorithmic persona is deployed to apply a “Gnostic” tag. Then his algo-possessed swarms are unleashed on the target.

A hardcore conspiracy theorist would say the ultimate goal is to make otherwise smart conservatives and Christians look stupid, vaporizing their long-term credibility.

But I’m not a conspiracy theorist, so I assume it’s all an elaborate prank.

I’ve invited Lindsay to discuss these matters in-person, both on social media and privately through a mutual friend. Assuming the good doctor hasn’t achieved gnosis—putting him above criticism—I now challenge him to a public debate.

Lindsay claims “Marxism is Gnosticism.” He says the latter believes “it is not you or your theories that are wrong, but the world itself” and that gnosis “will allow us to repair the world and ourselves.”

I argue this formula is a one-dimensional confusion of categories. Marxism is fundamentally materialist; Gnosticism is essentially spiritual. To conflate them is as shallow as it is misleading.

If I’m wrong, let him prove it in verbal combat.

A couple of weeks ago, a mutual friend sent both Lindsay and O’Fallon a link to my newly launched Omega Point Podcast. Apparently having no shame, Lindsay’s immediate response was to throw together an astonishingly ill-informed show of his own, entitled “Teilhard de Chardin and the Religion of Progress.” I’m tempted to rib him for mispronouncing “de Chardin”—rhyming it with “gay sardine”—but in my own inaugural episode, released last July, I rhymed his name with “they tardin’.” This is just the Tennessean’s curse.

Over the course of his bizarre episode, Lindsay reads long passages of Teilhard’s work—maybe for the first time—and pauses here and there to label Teilhard’s ideas “Gnostic,” “Hermetic,” and “Theosophical.” Displaying a cartoonish lack of self-awareness, Lindsay mocks Teilhard’s “sloppy thinking” and dismisses Teilhard as having “a conclusion seeking an argument.” Lindsay accuses Teilhard of making a “straw man” of evolutionary dynamics “so he can sound smart,” and calls him a “clown,” a “crackpot,” a “heretic,” and so forth.

This should embarrass Lindsay more than it irritates me. Maybe his entire career really is a clever prank. In any case, as a fellow Tennesseean, this guy is making us look ignorant.

Lindsay claims the Omega Point is a “collectivist” world where “everything and everybody are thinking the same thing.” He says Teilhard’s “Gnostic” “Theosophy” is “the exact same hermetic philosophy at the heart of Marxism.”

I argue this is another one-dimensional confusion of categories—a flattening of reality into Wiki-brained slop.

If I’m wrong, let him defend his assertions in public debate.

It’s important to emphasize that Lindsay, O’Fallon, and I have common enemies: globalism, communism, transhumanism, and the Devil himself. My problem is that these two are leading a quixotic charge. My reaction is to shake my damn head. My solution is to talk this out. In the best case scenario, their trigger-word thesis can be tempered by my antithesis, allowing us to arrive at a reasonable synthesis.

Honestly, I’ve learned a lot from James Lindsay. He has inspired much self-reflection and changed the way I report on my own subject matter. Whether he’s an atheist or an agnostic (or a little “g” gnostic), one passage in particular offers deep insight:

[T]heosophy, whether Marxist or otherwise, is Satan presenting himself as an Angel of Light until he creates a madness in those who follow him that way that possesses them with a spirit of enmity and false superiority presenting itself as righteousness and truth.

You can know them by their fruits, it is said. What are their fruits?

Entitlement. Narcissism. Self-aggrandizement. Accusation. Deception. Enmity. Sowing confusion, even in their own minds and hearts. Attempting to lead the little ones astray. Destruction, everywhere they go. It is Evil selling itself as uniquely Good.

This contains such ironic truth, I suggest we memorialize it as “The Iron Law of Woke Right Projection.” As a man thrashes at the demons out there, the demons within grow stronger.

SIGNED COPIES OF DARK ÆON ARE NOW AVAILABLE

Purchase yours at → DarkAeon.xyz ←

10% off with Promo Code: JOEBOT — until August 1st

“Be passers-by.” Excellent.

Joe, with every post you open up my mind to many mansions of info. Love it; Your fresh perspectives get my neurons hopping!Can't wait to read the book!! And don't forget about doing the

"Roadie tales " book and and anthology of your articles! Have a blessed day!!!